It's not if you win or lose, but how you spell the words

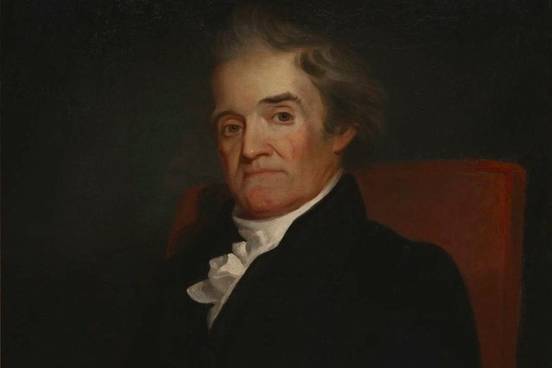

American English looks different from the English of its birthplace, aka Merry Old England. That's partly by design—often the specific design of our own Noah Webster, Merriam-Webster's direct lexicographical forefather. Many of these spellings existed before Webster, but he championed them in his 1806 A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language and his 1828 An American Dictionary of the English Language, and of those spellings that succeeded, his contribution to that success should not be overlooked. Of those that failed, well, there's still time.

WIN: mold

The wisdom in spelling cold as we do was long understood before Noah Webster's time, but we can credit him with the fact that mould as a spelling of mold has not had centuries to trip up American school children trying to also master could, should, and would. Webster dubbed the mould spelling "incorrect orthography" in his 1828 dictionary.

WIN: jail

We don't know if Elvis Presley ever acknowledged his indebtedness to Noah Webster, but we will note here that "Gaolhouse Rock" just doesn't look as rock 'n' roll as "Jailhouse Rock." Webster had fully committed to jail over gaol from the time of his 1806 dictionary. His choice had a solid pedigree: jail comes from Middle English jaiole, which in turn comes from from Anglo-French gaiole, jaiole.

WIN: draft

Thanks to Noah Webster, American English users don't have to explain to their children that draught rhymes with raft in direct contradiction to the much more common past tense forms of catch and teach: caught and taught. Webster himself included the form draught in a few definitions in his 1806 dictionary, demonstrating that spelling habits can die hard.

WIN: traveled

Noah Webster didn't include the past tense form of travel in his 1806 dictionary, but he did include traveller, with two "l's." By his 1828 dictionary, he'd decided on traveler and included the past tense form traveled as well, paving the way for Robert Frost to write the famous lines "I took the one less traveled by, And that has made all the difference."

WIN: magic

Since magical lacks a "k," it only makes sense (thought Noah Webster, and as far back as his 1806 dictionary) that magic too would go without a "k"—hence no magick in American English. The same reasoning gave us also our public and traffic spellings, as well as others. The words gimmick and haddock and maverick have no k-less relation (there is no gimmical, haddocal or maverical) to argue away their "k's."

WIN: center

Noah Webster appears to have had no doubts about including only the center spelling of this word in both his 1806 and 1828 dictionaries, despite the fact that Samuel Johnson included only centre in his 1755 dictionary. Johnson's choice was, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, likely based on a very particular edition of an earlier dictionary by one Nathan Bailey: while all 30 editions of Bailey's dictionary featured the "er" spelling of center (which was likewise used in editions of Shakespeare, Milton, and others), the folio edition of Bailey's dictionary was the one Johnson used, and it employed centre. Hence, today's British "city centre" and the American "shopping center."

FAIL: ake

How comforting would it be if ache were spelled to match the words with which it rhymes, such as bake and cake and take and wake. But no, despite Noah Webster's efforts, ache is the spelling we've got, and its contribution to headaches induces in us only the wannest of smiles. That it stands in orthographic affront to such susurrus words as ganache, mustache, cache, and panache is all the more tragic.

FAIL: soop

The soop spelling of soup had been kicking around for more than 100 years by the time Noah Webster was advocating for it. It would indeed make good sense if this word looked like its rhyming relations like coop, hoop, and loop. But Americans were having none of it: they insisted on maintaining the French-looking "ou" when considering the contents of their soup bowls. Webster also aimed for croop (for croup) and groop (for group), to no avail.

FAIL: spunge

While lunge did indeed fully replace longe for sudden forward movements in the spelling of American English users, spunge as a spelling of sponge has not soaked in. Both were put forward in Webster's 1806 dictionary, at which point lunge had only been extant in the language for a few decades. Sponge, on the other hand, dates back to Old English, and had been spelled with both "u" and "o" as its vowel over the centuries. Why sponge prevailed may have to do with its origins in Latin spongia, from Greek spongia, which were likely known to those schooled in science.

FAIL: wimmen, wimman

Noah Webster included the following entry in his 1806 dictionary:

Wimmen, n. pl. of wimman, to old and true spelling

But he'd abandoned that fight by the time of his 1828 dictionary, which includes nothing between its entries for wimbrel and wimple. The spelling we've been left with gives us the only English word in which the letter "o" sounds like \i\.

FAIL: tung

Noah Webster's assertion in his 1828 dictionary—"Our common orthography is incorrect; the true spelling is tung"—is not without merit: the word tongue descends from Old English tunge, and should by logic be spelled like lung and rung. Instead it has unreasonable vowel representation and two useless letters at the end. Don’t blame us.

FAIL: iz, waz

While neither "z" spelling of was or is made it into a Noah Webster dictionary, Webster used the forms waz and iz throughout his A Collection of Essays and Fugitiv Writings, published in 1790. He likewise employed in that same work hiz (for his), az (for as), cloze (for close), thoze (for those), and theze (for these). Deserve was rendered as dezerv and observe as obzerv. The same work shows the following as well: hav (for have), giv (for give), and proov (for prove).