Apocalypse

"Mulder and Scully were outsider heroes working within a corrupt government, and their questing to expose truth and squelch the apocalypse resonated with the alt-culture vibe and premillennial angst of the 1990s." —Jeff Jensen, Entertainment Weekly, 3 July 2015

When we hear the word apocalypse, a number of images run through our minds: fire and flood, earthquakes and tidal waves, crumbling societies, zombies. But when apocalypse came into English in the 1200s, it referred to none of these things.

Apocalypse was initially used to refer to a particular type of Jewish and Christian writing that was common between 200 BC and 150 AD and which used symbolic imagery usually to foretell the end of this world and the future to come. The best-known apocalyptic work is the Apocalypse of St. John of Patmos, more commonly called the book of Revelation.

The Greek word that gave us apocalypse means "to uncover" or "to reveal." You can see how the Apocalypse of St. John came to be called Revelation, then: the apocalyptic writings were so called because they revealed or uncovered future events.

Apocalyptic writings, and especially the Apocalypse of St. John, were often filled with cataclysmic events that heralded the end of this present age and the dawning of the age to come: fires, earthquakes, heavenly armies fighting. A few centuries after the word apocalypse entered English to name this style of literature, the word gained two additional senses: one that referred to the final battle between good and evil that's spoken about in the Apocalypse of St. John, and another to refer to any great disaster with far-reaching effects.

This last meaning, so far removed from the original use that referred to a type of literature, is now the most common use of apocalypse, and has even shown up in humorous portmanteaus—most notably in snowpocalypse to refer to a sizeable snowstorm.

Forbidden Fruit

A March 13, 2010 Wall Street Journal headline offered a nice play on "apple": "Forbidden Fruit: Microsoft Workers Hide Their iPhones."

Forbidden fruit names a pleasure that's immoral, illegal, or both.

In Genesis, God forbade Adam and Eve to eat the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. The serpent tempted them, they couldn't resist, so God exiled them from paradise. And here we are today.

What was the fruit? The usual suspect is apple. In Latin, malus means both evil and apple tree. Other contenders include grapes, figs, quinces, and pomegranates.

Feet of Clay

A king dreamed, a prophet interpreted, a phrase was born.

Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylonia, dreamed of a huge statue with a head of gold, silver torso, bronze belly ... and feet of iron and clay.

The prophet Daniel deciphered the king's vision, observing that the feet of clay signified weakness. (Daniel 2:42)

Daniel's revelation gave feet of clay its current sense: a character flaw not readily apparent.

For example, as one blogger pointed out, "Like the rest of us, Tiger Woods has feet of clay."

Back to Adam and Eve.

After eating the forbidden fruit, they knew that they were naked; and they sewed fig leaves together, and made themselves aprons. (Genesis 3:7)

God wasn't fooled, of course - and today a fig leaf refers metaphorically to something that conceals or camouflages (usually inadequately or dishonestly).

Fig leaves can also be used more literally. For example, art restorers in Italy long ago discovered that fig leaves in paintings and sculptures aren't always original. Sometimes they were added, centuries later, to conceal offending nudity.

Armageddon

Good vs. Evil. The Final Battle. The Ultimate Conflict.

This story, still thrilling, is as old as Armageddon.

The word appears only once in the Bible ("Then they gathered the kings together to the place that in Hebrew is called Armageddon"-Revelation 16:16). Armageddon names the site (or time) of the conclusive battle between the forces of good and evil.

These days, the word can be applied to any vast decisive confrontation. For example, the battle over health care legislation was dubbed an Armageddon.

And of course the word's end-of-the-world implications can also be seen, winking, in winter storms labeled snowmageddon.

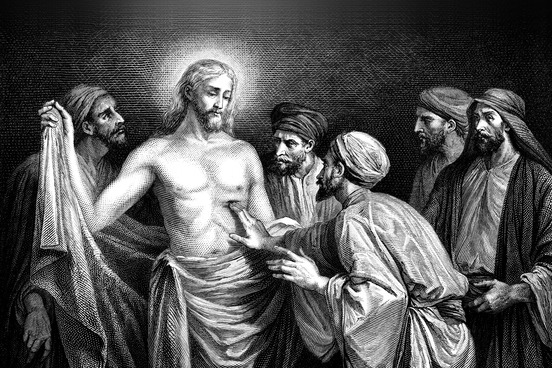

Doubting Thomas

Thomas the Apostle claimed he wouldn't believe in the resurrection until he actually touched the wounds of Jesus.

Jesus understood Thomas' doubt and invited him to do just that. But according to the Gospel of John, Jesus also included this gentle rebuke: blessed are they that have not seen, and yet have believed. (John 20:29)

Either way, Thomas lost his doubt. But doubting Thomas came to name any incredulous or habitually doubtful person.

For example, consider the person on Twitter who confessed, "I am slowly turning into a doubting Thomas about social media."

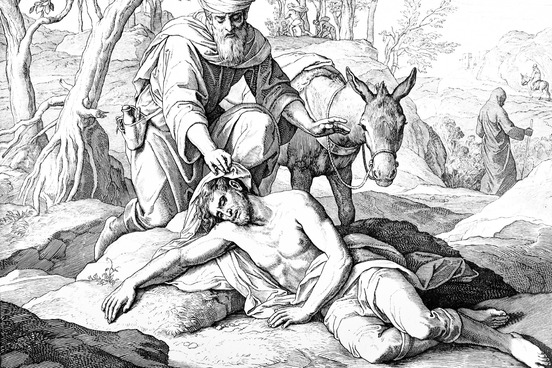

Good Samaritan

"A good Samaritan was assaulted early Sunday morning ... after picking up a man whose truck had broken down." -The Paris [Tennessee] Post-Intelligencer, Mar. 2010

This is a sorry twist on the original episode.

In Luke 10:30-37, Jesus told a parable about a man traveling from Jerusalem to Jericho who was robbed, beaten, and left for dead. Though the man was probably a Jew, a priest and a Levite hurried past. Only a Samaritan (a people who had hostile relations with Jews) stopped to help.

Good Samaritan now names someone who generously aids those in distress. Good Samaritan Laws protect persons who, in good faith, render emergency care.

Kingdom Come

It's odd that kingdom come is often associated (sometimes humorously) with violent death.

For instance, as one blogger reported, "Turns out that in foiling a plot by the evil Nazi scientist Baron Zemo, Captain America's teenage sidekick was blown to kingdom come."

But the phrase comes from the Gospel of Matthew, which includes these words in The Lord's Prayer: Thy kingdom come,/Thy will be done ... (Matthew 6:10)

Kingdom come is heaven, or the next world - a place, one hopes, of absolute peace.

Shibboleth

Mispronouncing a word can be embarrassing; in this case, it could be fatal.

Shibboleth means "stream" in Hebrew. In the Book of Judges, following a great battle, Gileadite soldiers challenged suspected retreating Ephraimites to say it - because they knew their Ephraimite enemies could not pronounce sh. As the story goes, 42,000 Ephraimites failed the test and were killed.

Over the years, shibboleth has lost its danger.

Today, it usually describes a trite idea or platitude, or a slogan or catchword.

For example, in an article poking fun at contemporary food trends: "Words like seasonal, local and, best of all, green market were shibboleths for every self-respecting cook from potato peeler on up." (Time, Feb. 2010).

Begats

"Your mother told you I would be writing your begats, and you seemed very pleased with the idea." —Marilynne Robinson, Gilead, 2004

Another word that doesn't appear often in print, but often enough to merit entry into our Unabridged Dictionary, is begats. It is used informally to refer to a genealogical list, as Robinson uses it above, or to one's offspring. This word comes ultimately from the verb beget, which is a formal and somewhat archaic word that means "to become the father of (someone)."

Genealogies are important throughout the Jewish and Christian Scriptures: they give a historical context to stories being told, and establish spiritual lineages through which God's promises, blessings, and curses are enacted through history. Accordingly, there are some extensive genealogies in the Bible, and particularly in the Jewish Scriptures:

And Attai begat Nathan, and Nathan begat Zabad, and Zabad begat Ephlal, and Ephlal begat Obed, and Obed begat Jehu, and Jehu begat Azariah, and Azariah begat Helez, and Helez begat Eleasah, and Eleasah begat Sisamai, and Sisamai begat Shallum, and Shallum begat Jekamiah, and Jekamiah begat Elishama. —1 Chronicles 2:36-41, KJV

These long lists became humorously known as begats, for frequent repetition of the word. We've been using begats to refer to genealogies since the late 1800s.

MORE TO EXPLORE: 11 Words from the Bible You Didn't Know Were Biblical