Quire

A quire was originally a small medieval book or pamphlet, especially one constructed of a set of four sheets of paper folded in two, forming eight leaves. The quire grew in time, and it came to be a collection of 24 (sometimes 25) folded or unfolded sheets, which makes a ream of 480 sheets of paper 20 quires, and a quire one twentieth of a ream. (Ream in this sense is from Arabic rizma, which literally means "bundle"; the verb ream with the slangy sense of "reprimand" may come from a Middle English word meaning "to open up," but that's an educated guess so don't ream us out if it turns out not to be true.) Quire is ultimately from Latin quaterni, meaning "set of four," and entered Middle English via Anglo-French.

For those who might be contemplating the similar pronunciation of quire and the "singing" choir, quire is actually an archaic variant of the word. Choir is also derived from Anglo-French: it is from queor, a French formation derived from Medieval Latin chorus, referring to a company of singers in church or the area in which they sing. Quire was often used in English as a variant of choir up to the close of the 17th century.

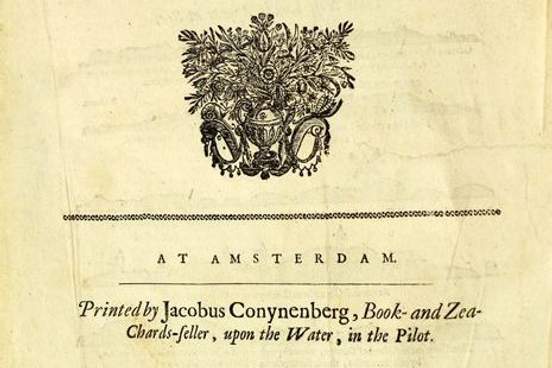

A colophon, whose name is from a Greek word meaning "summit" or "finishing touch," is traditionally an inscription placed at the end of a book or manuscript, usually with facts that relate to its production. These details might include the name of the printer and the date and place of printing. Colophons are found in some manuscripts and books made as long ago as the 6th century AD. In Medieval and Renaissance manuscripts, a colophon was often added to provide facts such as the author's name and the date and place of the completion of the work, as well as an expression of thanks to those who assisted in its production.

Eventually, the colophon was included on the blank page opposite the title page where it consists of usually a one-sentence statement as to where the book was printed and by whom. It also can be a simple identifying mark, emblem, or device that is used by a printer or a publisher on the title page, cover, spine, or jacket. Whatever the case, they remain a neat feature to discover when perusing books in a used book store.

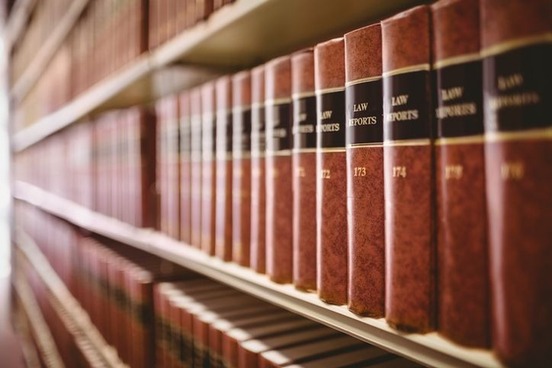

Spine

Spine goes back to the 15th century, and it is derived from Latin spina, which can mean "thorn" or "backbone" (which are also two of the original meanings of spine in English). The word was first applied to the back of a book to which the pages are attached—or the part that shows as the book ordinarily stands on a shelf that is often lettered with the title and the author's and publisher's name—in the early 20th century. Along with back, the spine of a book might be also called the backbone, backstrip, or shelfback.

The title on the backbone, being functional as well as decorative, is of paramount importance.

— R. R. Donnelley and Sons Company, All the King's Horses, 1954These backstrips, which were usually without bands, contained at the top the title of the books and at the foot the motto, spes mea deus.

— Meiric K. Dutton, Historical Sketch of Bookbinding, 1926This volume breaks all the patterns: the cover is paper-covered boards with a cloth shelfback, and the dust jacket echoed the cover.

— Kari A. Ronning, Studies in the Novel, 22 Sept. 2013

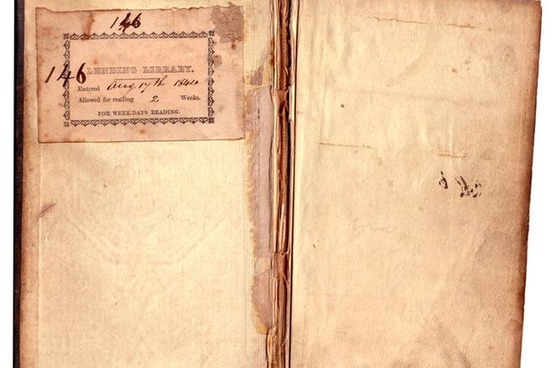

Ex libris

In Latin, ex libris means, literally, "from the books," and, in the past, the phrase was placed before the owner's name on a bookplate. In the late 19th-century, the phrase came to refer to the bookplate itself, which is a label that identifies the owner of the book, is usually engraved or printed, has a distinctive design (for instance, the owner's coat of arms), and is pasted to the inside front cover of a book.

In Latin, liber meant "book." That word gave English the word library in the 14th century. To remember the meaning of ex libris, you might think of it as meaning "from the library of (that person who lent you the book)."

Gutter

The area where the inside margins of adjoining pages of a book meet is called the gutter. For obvious reasons, the gutter must always be wide enough to permit the innermost text to be read easily when the book is bound.

In Middle English, the word gutter referred to any watercourse, in general, before specifying a brook and then a type of trough to catch and carry off rainwater on a street or from a rooftop—and, later, one that carries a misthrown bowling ball.

The word coursed into English via Anglo-French gutere or guter, derived from gute, meaning "drop" as well as "gout." The disease known as gout, which causes painful swelling of the joints especially in the toes, gets its name from the antiquated notion that the disease was caused by drops of diseased humors. Actually, it is caused by the deposit of uric-acid salts, which are normally excreted in urine, in joints.

Page

A page was a youth in medieval Europe who served an apprenticeship in the duties of chivalry in the family of a man of rank. He began as an assistant to a squire in the hope of becoming a squire himself and then advancing to a knight.

As a page, Wart had learned to lay the tables with three cloths and a carpet, and to bring meat from the kitchen, and to serve Sir Ector or his guests on bended knee.

— T. H. White, The Sword in the Stone, 1938

Like the youthful, but lexically older, page, the bookish page is a derivative from French, but it ultimately goes back to Latin pagina, which is akin to the Latin verb pangere, meaning "to fix" or "to fasten." The connection comes from strips of papyrus being "fastened" together to form a writing surface. The English word paper also has a connection: it, too, enters English via French and is from Latin, and its Latin origin is papyrus.

The verb page in senses denoting service as an attendant or messenger is older than the verb referring to the numbering of the pages of a book or turning pages, as in "paging through a magazine." "Page boys" were being "paged," or being called upon, by the early 20th century, and by the 1930s, people were being "paged" via radio or intercom. The predecessor of the pager as a device used to signal someone via beeps, vibrations, or flashes about an incoming message enters English about mid-1900s. Fast-forwarding, talk about a computer "page" began in the 1970s, and "home pages" and "web pages" in the 1990s.

Folio

In printing, a sheet of paper folded in half is called a folio. The name is from Latin folium, meaning "leaf." The term folio can also refer to a book of large size. The collected works of William Shakespeare, for example, were first published in a folio edition in 1623. Eighteen of Shakespeare’s plays were printed in quartos (books about half the size of a modern magazine) before that publication. The quartos are seen as defective editions of the Bard's work, marred by badly garbled or missing text. In printing, a quarto refers to a sheet of paper folded in fours or the book itself composed of bound quarto signatures. (Signatures are printer's sheets folded to form one unit of a book; a book is a collection of signatures that are bound together.)

Folio can also refer to a page number, and the numbers may be prominent or unobtrusive—in other words, they could be placed prominently at the top, the center, or the outside margin of the page, or they could be unobtrusively placed at the bottom or the gutter margin. A more common sense of folio refers to a case or folder for loose papers.

Another "leafy" page in publishing is flyleaf, which refers to one of the free endpapers of a book. An endpaper is a folded sheet pasted against the inside front cover, but sometimes the back, and forms the first or last free page of a book with the other half.

Volume

When you want to rock out to your favorite tune, you reach for the volume knob or button, but when you want to find out how sound travels through the air to your ears, you might reach for a volume of an encyclopedia (at least, in pre-internet days). So, what's the connection between those senses of the word volume?

Volume comes from the Latin noun volumen (meaning "roll"), which, in turn, derives from the Latin verb volvere ("to roll"). The Roman volumen was essentially a book rolled up on a short staff. The reader held the roll in one hand and, once he or she had read a column, rolled it onto another cylinder with the other hand.

The French borrowed the word from Latin, changing it to volume, and in the 14th century, the English acquired the word from the French. At first, volume simply meant "book," but by the 16th century, it had also come to refer to a book that is a part of a series of books. From there, the word was extended to the generalized sense meaning "the quantity, amount, or mass of anything," and in the 18th century, volume acquired the meaning "strength or intensity of sound."

Bibliography

Bibliography commonly refers to the alphabetized listing of books, magazines, articles, etc., that are mentioned in a text. Additionally, it can refer to a listing that is more detailed, or "descriptive," about the references, or it can refer to a critical or analytical study of books as tangible objects themselves.

A descriptive bibliography may take the form of detailed information about a particular author's body of works or about works on a given subject. Critical bibliography, on the other hand, involves meticulous descriptions of the physical features of books, including the paper, binding, printing, typography, and production processes that are used to help establish such facts about a book as its date of publication and its authenticity.

Bibliography dates to the 17th century, and it likely developed from New Latin bibliographia, itself derived from the Greek word for "the copying of books," a combination of biblio- ("book") and -graphein ("to write").

Appendix

Supplementary matter that forms a cohesive whole is often found in an appendix. A book may have a single appendix or more (which, in such cases, will usually be headed "Appendix A," "Appendix B," etc.). The appendix may consist entirely of the author's prose, or it might consist of a table, list, document, or something else.

The word appendix is from Latin appendere, meaning "to be attached," and goes back to the 16th century. In English, it refers to things connected or joined to something larger or more important, like the back matter of a book added to the main text. The tube that is located at the bottom of a balloon to inflate it is also called an appendix. Both plural forms of the word, appendixes and appendices, are standard in technical and nontechnical contexts.

The anatomical appendix, the narrow tube at the beginning of the large intestine, is technically referred to as the "vermiform appendix" (in Latin, vermis means "worm"). The vermiform appendix is not essential and can be removed if it becomes inflamed. A book's appendix is also not essential to a book's main text, but it gives additional support to the writer's claims.

Chapter

In Middle English, chapter was often spelled chapitre. That spelling is taken directly from an Anglo-French word that is based on Late Latin capitulum—ultimately from caput, meaning "head," and itself meaning "division of a book," which is the common meaning of chapter in English.

The phrase "chapter and verse" in reference to providing exact information or details about something goes back to the early 17th century and, rather unsurprisingly, comes from the tradition of citing exact biblical passages by their chapter as well as their verse number.

Chapter was also used in Middle English for a meeting of clergy members, which was frequently opened with the reading of a chapter from the Scriptures. This sense of chapter eventually evolved into today's sense referring to the body of a local branch of an organization, as in "chapters of the American Red Cross" or "chapters of the fraternity."

Epigraph

Epigraph refers to a short quotation from another source placed at the beginning of an article, chapter, book, etc., that alludes to what's to come in your reading. Its attribution is generally set by itself on the line below the quotation. Alternatively (if print space is a concern), it is run in on the last line of the quotation. When set on its own line, it is generally preceded by an em dash or, less frequently, it is enclosed in parentheses.

Here are a couple examples of famous epigraphs:

Did I request thee, Maker, from my clay / To mould me Man? Did I solicit thee / From darkness to promote me?

— John Milton, Paradise Lost (in Mary Shelley's Frankenstein)Lawyers, I suppose, were children once.

— Charles Lamb, "The Old Benchers of the Inner Temple" (in Harper Lee's To Kill a Mockingbird)

The word epigraph is derived from Greek epigraphein, meaning "to write on" or "to inscribe," and was written into the English lexicon in the 17th century, originally as a word for an inscription engraved on buildings, tombs, statues, or other objects, such as coins (as in "In God We Trust," which is an epigraph on U.S. coins).

Skiver

Skiver is an early 19th-century word that refers to a thin, soft leather made of sheepskin that is tanned in sumac and dyed. In the past, it was used for hat linings, pocketbooks, and bookbindings. Its name is probably derived from Scandinavian skive, a verb meaning "to cut off (as leather or rubber) in thin layers or pieces."

Readers might be familiar with skivvies as a word for "underwear," or maybe even skivvy, an early 20th-century term for a female domestic servant in British English. They are unrelated.

Preface/Foreword/Introduction

An author's prefatory remarks that explain the object and scope of what follows are usually titled "Preface," which is appropriate since the word preface comes from Latin praefari, meaning "to say beforehand." For works of literature, prefaces can sometimes be extended essays, such as those of Henry James and George Bernard Shaw. The preface often closes with acknowledgements of those who assisted in the writing, and it is usually signed (and the date and place of writing sometimes follow the typeset signature).

When a person other than the author writes an introductory essay, it is normally titled "Foreword" (which denotes words said before something else and is presumably from a translation of German Vorwort); the author's preface, if any, then follows it.

Another type of prefatory matter is the "Introduction." The introduction contains information that is essential to the main text and that may be paginated in Arabic numerals. In reference works, such as a dictionary, a section of explanatory notes concerning content and format might be included in the front matter.

Vellum

Vellum is from Middle English velym, borrowed from Anglo-French velim, which itself is related to an adjective meaning "of a calf" and a noun meaning "calf." The word is also related to veal.

Vellum, in printing, refers to the skins of calf, kid, or lamb prepared as parchment for writing on or for binding books. The term is also used as a synonym of parchment. The production of parchment facilitated the success of the codex, an early type of manuscript consisting of a collection of pages stitched together along one side that replaced earlier rolls of papyrus and wax tablets.

In modern usage, the terms vellum and parchment are sometimes applied to a type of cream-colored paper of high quality that is made chiefly from wood pulp and rags and having a special finish; they also refer to vegetable parchment, which we now call simply parchment paper and use in cooking. Additionally, they refer to translucent paper made for tracing purposes.

Addendum

Addendum refers to something that is added; specifically, it refers to a section of a book added to the main or original text that might include explanation, comment, or supplementary material. It comes from a Latin word of the same meaning, and it is often used in its Latin plural form addenda (as opposed to addendums) when it is applied to a supplement of a book.

In mathematics, the related addend, which is a shortening of addendum, refers to a number or quantity to be added to a preceding one or to a sum already accumulated. 4 and 9, for example, are addends in 4+9 = 13.

Index

Index refers to a usually alphabetical list that includes all or nearly all items (such as authors, subjects, or keywords) that are considered pertinent and are discussed or mentioned in a book, catalog, etc., or an electronic database. An index gives with each item the location of its mention in the work, and it is located at the end of the work. The word, as well as this sense, goes back to the 16th century, and it is from the Latin verb indicare, meaning "to point out" or "to indicate," which explains why the forefinger is also called the "index finger" and, in economics, we have such terms as the "consumer price index" and "retail price index," both of which indicate changes of prices over a given period of time.

In the "book" sense of the word, the plural indexes is preferred, but the Latin plural form indices is also acceptable.