When we think of classic scams and capers they generally hew to certain basic rules: card games, horse racing, or stock market shenanigans are often involved, and, should a movie be made about the exploits of a confidence man or woman, the protagonist will be well-groomed, charming, and possessed of the sympathies of the audience. While we have no desire to challenge the structure of this genre, we are compelled to point out that there is an old and venerable version of the con that has been notably overlooked by Hollywood: the Infortunate Dictionary Scam.

The earliest evidence of this particular scam is credited to a group called the "Learned Dandies" in 1818.

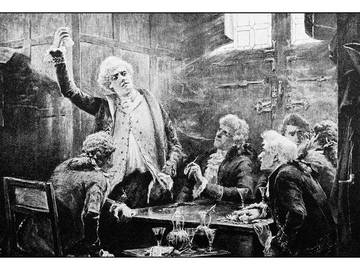

This particular routine is little used these days, so it's understandable if you've never heard of it. All that's required is a confederate or two, a crowd of peevers who are inclined to wager, and a suitable dictionary. The swindle has many small variations, but the form is always more or less the same: two or three people (who pretend to not know each other) enter an establishment (preferably one where people are drinking), and one of them repeatedly and clearly uses the word infortunate. One of the other swindlers will challenge the speaker, and make a bet that unfortunate is the correct word, and that infortunate does not exist in the English language. The first speaker accepts the bet, and agrees to place similar wagers with anyone else who cares to bet against infortunate. Some portion of the tavern readily agrees, the bets are placed, at which point the swindler pulls out a copy of a dictionary which defines infortunate, collects the winnings, and decamps.

The earliest evidence of this scam we have appears in 1818, when a concerned citizen, using the name Veritas, wrote a letter to the London newspaper The Morning Post, warning of a group that the letter writer referred to as “Learned Dandies.” One of the Dandies ostentatiously dropped the word infortunate in conversation, provoked a bet, then adjusted his cravat, pulled out a copy of Samuel Johnson's dictionary, and demonstrated the word’s existence. The letter writer stated that after this the Dandy “with the greatest composure pocketed the money and walked off, leaving us to console one another on our folly, and I may add, stupidity.”

This swindle worked quite well because people would assume that infortunate was not a word, and it is. It's a now-archaic synonym of “unfortunate,” and is actually substantially older than its common variant. The Oxford English Dictionary records infortunate in use since the late 14th century; our earliest record for unfortunate comes approximately 100 years later.

…but I truste she wylle haue pyte vpon me at the laste

for loue causeth many a good knyght to suffre to haue his entent

but allas I am vnfortunate.

— Thomas Malory, Le Morte Darthur, 1485

There are accounts of the Infortunate Dictionary Scam throughout the 1820s and 1830s. In some respects it sounds rather apocryphal, as the same word is always used, and how many people fall for this bit? Quite a few, as it turns out. Thomas Wontner, in his 1833 book Old Bailey Experience giving what is perhaps the most thorough explanation of the scam, claims that one group swindled people this way for years.

Three men travelled the country and supported themselves in extravagance for nearly three years by the word—infortunate. When they entered a town they took up their abode at separate inns, or public-houses, as if unknown to each other; they then frequented the rooms where the tradesmen of the place resorted to enjoy themselves, where they would wait an opportunity for a full room of company, in a state of hilarity and super-excitement: the word infortunate would then be used by one of the confederates in some purposely-constructed sentence, the correctness of the word would be immediately questioned by another of the party, and bets to a pretended large amount staked on both sides, as to whether or not it was a dictionary word. It was the object of these itinerant swindlers, in course of their affected controversy, to draw in all the persons composing the party to oppose, and lay wagers, that there is no such word as infortunate in the English language. When this was accomplished, a dictionary was called for, and the word pointed out to the assumed surprise of the confederates, whilst the man, learned in dictionary lore, pocketed the cash. Simple as this mode of raising money may appear, it had a great run in the country.

— Thomas Wontner, Old Bailey Experience, 1833

Court records and newspaper accounts of the time identify at least two distinct groups of these sharpers by name: John Fearly and Joseph Wood, and the trio of Thomas Baxter, Thomas Shuttleworth, and William Brotherton. Word must have eventually gotten out, or the sharpers must have been imprisoned, as there is little evidence of continued applications of this con after the 1830s (save for a brief flurry of articles in the US describing someone who resurrected the routine in the early 20th century, apparently more for amusement than money).

We are presenting this overlooked chapter in the history of flimflam for two reasons. First, so that if you overhear someone loudly and repeatedly using the word infortunate in your local watering hole you do not wager money with them, and second, as inspiration for any screenwriters who need a plot device for a heist/scam/caper that's not a rehashed version of “charming protagonist steals money from unlikeable villain; hilarity ensues.”