"Bastard Brat of a Scotch Pedler"

Alexander Hamilton, the man whose image graces our ten-dollar bill, was born out of wedlock in 1755. A number of his political opponents made sure to remind the world of the circumstances of his birth. Perhaps foremost among these opponents was John Adams, who appeared to harbor a special dislike for Hamilton. Adams had a special expression that he came up with for Hamilton: "bastard brat of a Scotch pedler.”

Yet I loose all Patience, when I think of a bastard brat of a Scotch Pedler, daring to threaten to undeceive the World in their Judgment of Washington, by writing a history of his battles and Campaigns.

—Letter to Benjamin Rush, 25 January 1806Shall I replace on the Shoulders of Washington the burthens that a bastard Bratt of a Scotch Pedlar, placed on his Shoulders, and he Shifted on mine?

—Letter to Thomas Jefferson, 12 July 1813When Perfidy and Treachery, Imbecility, Ignorance Fanaticism and Fury Surrounded Us; all, Puppets danced upon the Wires of a Bastard Bratt of a Scotch Pedlar.

—Letter to John Quincy Adams, 20 May 1816

According to the technical sense of the word, Hamilton was indeed a bastard. Whether he was a brat is, however, subject to debate.

"A Drunken Trowser-Maker”

The Detroit Free Press, late in 1868, published comments about Ulysses S. Grant that they attributed to "leading Radicals": “Grant is a Drunkard”; “Grant is a man of vile habits, and of no ideas”; “I am going to Europe to get out of advocating this bungler”; “Never ask me to support a twaddler and trimmer for office”; “The nation owes it to its self respect to tolerate imbecility in politics no longer”; “Grant is as brainless as his saddle.”

The notion that Grant was overly fond of imbibing has been talked about quite a bit. Less examined is how colorful some of the charges were. The Cincinnati Enquirer, in 1866, gave an account of a citizen at a meeting who alleged that Grant was nothing more than “a drunken trowser-maker.” Drunken has survived to this day as a term of invective; trowser-maker, regrettably, has not.

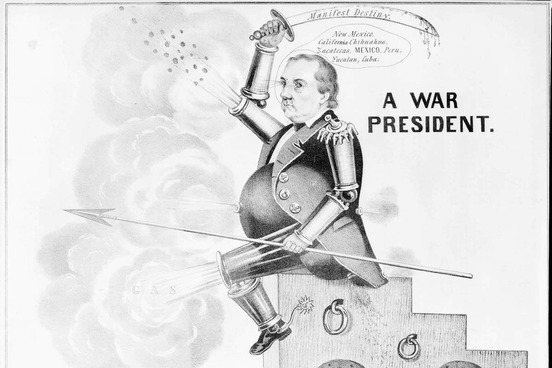

"Pot-bellied, mutton-headed, cucumber-soled"

Lewis Cass, who ran unsuccessfully as the Democratic candidate for president in 1848 (he lost to Zachary Taylor), did not receive so much invective as to make him a particularly notable candidate. But he did manage to earn the dislike of Horace Greeley, and Greeley happened to own a newspaper, The New York Tribune (and was not shy about using it for political ends). The Tribune referred to Cass as a man “whose life has been spent in grasping greedily after vast tracts of land, buying up large estates round Detroit, &c. and selling them out in small town lots, huckster fashion, at immense profits to tradesman and immigrants.”

Yet Greeley appeared to save his truly memorable insults for his personal correspondence. In a letter to Schuyler Colfax in 1848, he wrote of the candidate as “that pot-bellied, mutton-headed, cucumber-soled Cass.” Potbellied is fairly self-explanatory, and known to many people; muttonheaded refers to an oafish or dimwitted state; cucumber-soled has not, to the best of our knowledge, been used by anyone save Greeley, and its meaning remains shrouded in mystery.

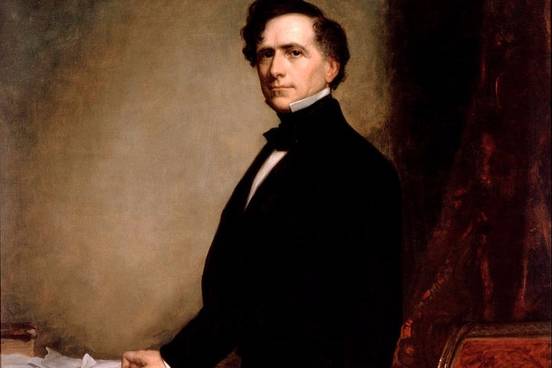

"Pimp of the White House"

Pimp is not a new word; it has been used in English since at least 1600 to refer to a criminal who facilitates liaisons with a prostitute. It has never been considered a polite word. So there was a certain degree of astonishment when, in 1855, Kenneth Rayner (a former Congressman from North Carolina) gave a speech in which he referred to President Franklin Pierce as one such creature:

“The minions of power are watching you, to be turned out by the pimp of the White House if you refuse to sustain him. A man sunk so low we can hardly hate. We have nothing but disgust, pity, and contempt.”

—The Weekly Standard [Raleigh, NC], 4 July 1855

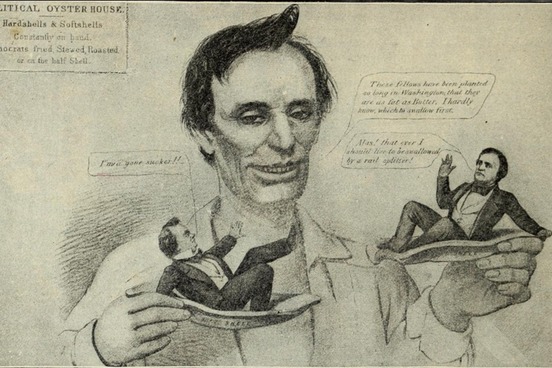

"Nightman"

It seems safe to say that a number of people did not like Abraham Lincoln. He was subject to more obloquy than most politicians, although few received insults as odd and drawn out as the one that was published in the Charleston Mercury on June 7th, 1860: “A late Harper’s Weekly we have received (May 26), gives us a portrait of Abraham Lincoln, the nominee, for President...; and a horrid-looking wretch he is!—sooty and scoundrelly in aspect; a cross between the nutmeg dealer, the horse-swapper, and the nightman.”

Horse swapper would appear to be a variant of horse trader; nutmeg dealer is possibly related to the supposed practice that some Yankee peddlers had of selling fake nutmeg, either by adding sawdust to the spice, or by carving the nutmeg seed itself out of wood. Nightman is the term for a person who empties privies by night.

In 1864, Harper’s Weekly helpfully published an article which contained a small compendium of some of the insults that had been lobbed Lincoln’s way: “Filthy story-teller, Ignoramus Abe, Despot, Old scoundrel, big secessionist, perjurer, liar, robber, thief, swindler, braggart, tyrant, buffoon, fiend, usurper, butcher, monster, land-pirate, a long, lean, lank, lantern-jawed, high-cheeked-boned, spavined, rail-splitting stallion.”

"General Jackson’s Mother Was a Common Prostitute"

One might possibly assume that the 19th century was in fact a more polite political climate than today, and so a thing such as calling a candidate’s mother a prostitute would be out of bounds. One would be wrong. The Cincinnati Gazette was reported to have published, in 1828, an article which alleged this very thing.

"General Jackson’s mother was a common prostitute, brought to this country by the British soldiers! She afterwards married a mulatto man, with whom she had several children, of which number General Jackson is one!"

Additionally, supporters of Jackson’s opponent, John Quincy Adams, drew attention to the fact that when Jackson married his wife Rachel, she had not technically been divorced from her previous husband, and called her an adulteress.

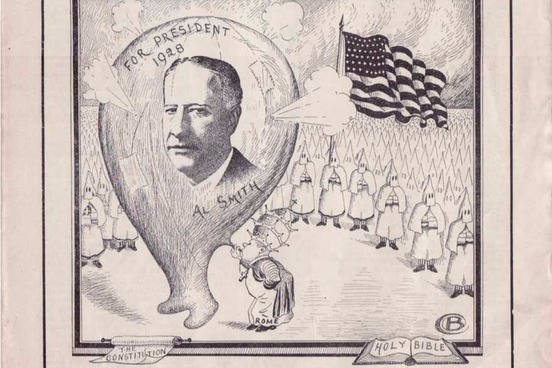

"The Wet, Romish, East Side, Tammany Hall Candidate"

Alfred E. Smith served as the Governor of New York State for four terms, and in 1928 was the first Catholic candidate to seek the presidency of the United States. Smith’s religious affiliation attracted a great deal of invective. One of the epithets often hurled his way was Romish, a disparaging term for Roman Catholics.

In April of 1928, the Baltimore Sun gave an account of a speech by Thomas Heflin, a senator from Alabama, in which he called for opposition to Smith’s candidacy:

“If Alfred E. Smith, the wet, Romish, East Side, Tammany Hall candidate, is nominated it will be on account of the Roman influence. In Houston I will use all my influence, all my power of speech to prevent his nomination, but if he succeeds it will mean that the Pope’s agent is in the White House. And such a man cannot be a good American.”

"Moral Leper"

Grover Cleveland served two terms as president, from 1885-1889, and 1893-1897. He received a fair amount of abuse in each campaign (as well as when he ran, unsuccessfully, in 1889). Perhaps the most memorable dig against Cleveland was the assertion that he had fathered an illegitimate child some years earlier; his opponent’s supporters took up the chant “Ma, Ma, where’s my Pa?” Although these charges did not prevent Cleveland from winning the office, they allowed a number of people to comment unfavorably on his character.

“Editor William Purcell of the Rochester Union and Advertiser, who resigned control of his paper rather than support Grover Cleveland, was at the Gilsey House to-day. When asked why he refused to support the Democratic nominee he said: ‘It is not on either personal or political grounds. It is because I believe him to be a moral leper.’”

—The San Francisco Chronicle, 26 July 1884

This was far from the only mean thing that was said of Cleveland. Senator Ben Tillman gave a speech in 1896 in which he referred to the President as a "besotted tyrant," and the "corrupt tool of Wall Street."

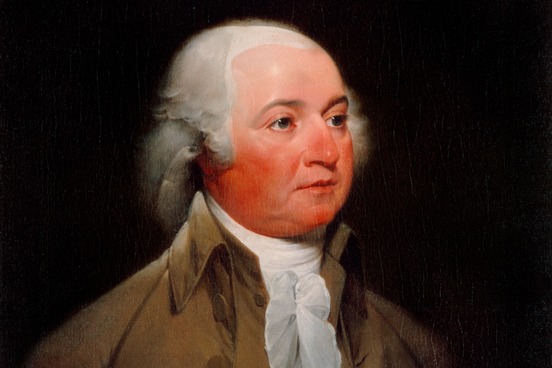

"Hermaphroditical"

The presidential election of 1800 was not genteel. John Adams, the incumbent, ran against Thomas Jefferson, and neither party came out looking dignified. One of the more vitriolic charges was leveled at Adams, after Jefferson allegedly hired the journalist James Thomson Callender to write unpleasant things about his opponent. Callender set to his task with gusto, and published an attack on Adams which stated that he was “a hideous hermaphroditical character which has neither the force and firmness of a man, not the gentleness and sensibility of a woman.”

Hermaphroditic refers to an animal or plant that has both male and female reproductive organs, or to something that is a combination of diverse elements. It is the adjectival form of hermaphrodite, a word which comes from Greek mythology: Hermaphroditos was the name of the son of Hermes and Aphrodite who joined his body with that of the nymph Salmacis and took on the characteristics of both genders.