Mustache

or moustache : the hair growing on the human upper lip; especially : such hair grown and often trimmed in a particular style

Some of the great questions in our culture may never be answered to the satisfaction of all. For example: Is a hot dog a sandwich? Perhaps we should take solace in the knowledge that some pressing questions have been resolved to the satisfaction of the English-speaking world—instances in which we have, in effect, voted with our words, whether knowingly or not.

Such a question is the once-burning issue of whether to consider the hair grown on the upper lip a singular entity or something split in two by the nose (or, if you’re inclined to use the specific anatomical term for the vertical groove of the upper lip, the philtrum. In other words: is mustache, linguistically speaking, properly singular or plural?

Many of the early recorded uses are plural, which allowed for a parallel with whiskers as a way to refer the long projecting bristles growing near the mouth of a cat:

My Tuskes more stiffe than are a Cats muschatoes.

— Thomas Dekker, Noble Spanish Soldier, 1634

But usage eventually settled by the late 19th century: the French-derived mustache or moustache (which has become the preferred spelling in British English) for generic references to upper-lip growths, and mustachios or, less commonly, the singular mustachio, when special emphasis on the size or grooming is made.

While the only thing required to grow a moustache is the passage of time and some appropriately placed hair follicles, honing that moustache into a fine facial accessory requires some particular knowledge, skill and equipment.

— Rufus Cavendish, The Little Book of Moustaches (Summersdale, 2014)

Dundrearies

: long flowing side whiskers

There’s nothing dreary about dundrearies (behold their straggly yet luxurious magnificence!), nor about the word dundrearies, named after Lord Dundreary, a character in the 1858 play Our American Cousin as portrayed with wackiness (and wacky whiskers) by English actor Edward A. Sothern. What is dreary is the fact that Our American Cousin was the play President Abraham Lincoln was attending when he was assassinated seven years later.

… and He mixed up a toddy and Mr. Pierce pulled at his dundrearies and Mrs. Black smoked the little brown cigarettes one after another and everybody was very jolly with Fra Diavolo playing on the phonograph and the harbor smell and the ferryboats…

— John Dos Passos, The 42nd Parallel (Harper & Brothers, 1930)

Galways

: whiskers following the line of the chin from ear to ear

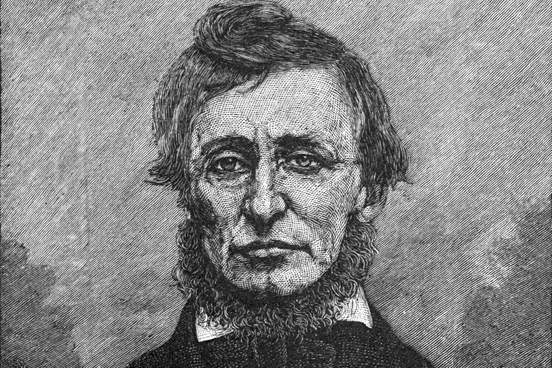

We’re not sure how popular “Galways” once were in actual County Galway, Ireland, but perhaps chin-hugging beards truly were the style of the time (you know, like tying an onion to your belt). However, as the third edition of our Collegiate Dictionary (1916) lists Galways as “U.S. slang,” it may be just as likely that the look—famously employed by none other than Henry David Thoreau—reflected only Americans’ imagining what their beard-growing counterparts across the pond were up to.

He is a selfish sort of duffer; he cares not how his fellows suffer, so he gets air shipped fresh from Finland, or other ozone markets inland. If he is in an office working, at keeping books, or merely clerking, he wants a window open always, so Arctic winds may frost his galways. And he will chortle as he freezes, among refrigerated breezes, “Oh, jiminy, but this is splendid! Fresh air sees all our ailments ended!”

— Walt Mason, The Farm Journal, January 1915

Muttonchops

: side-whiskers that are narrow at the temple and broad and round by the lower jaws

The first-known recorded use of muttonchops to describe facial hair rather than food occurred in 1865, spurred by the observation that this particular style of side-whiskers resembled a particular cut of not pork or even lamb, but specifically mutton, that is, mature sheep. However, in 1936 a little periodical with which you might be familiar called Time Magazine listed the less specific (and much, much more French) côtelette as a synonym for this type of sideburn. The same clipping, about the hirsutal happenings in the village of Bishop Hill, Illinois (then pop. 208, now pop. 114), also mentioned “the Newgate Fringe, a half moon of whiskers about a bald face,” as well as “the barbiche, a short beard covering the entire chin…”

Quietly, his eyes flitting around the room, he rolled a cigarette with one hand while fiddling with the monstrous ginger-colored walrus moustache he sported, so expansive it nearly touched the shaggy muttonchops he'd stolen from Grover Cleveland, though I doubted his knowledge of American presidents went back to the previous century.

— Ed Ifkovic, Café Europa : An Edna Ferber Mystery (Poisoned Pen Press, 2015)

Charley

: a short pointed beard

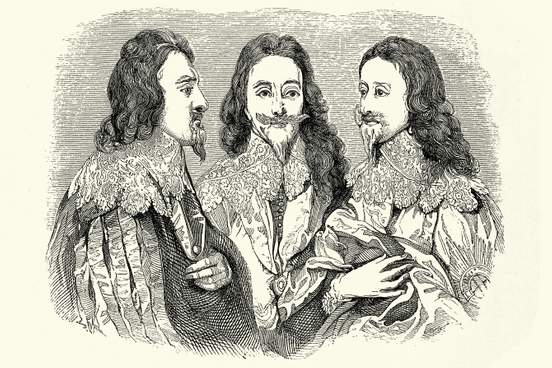

When people aren’t naming beards after meat or counties in Ireland, they’re often busy as all get-out coining eponyms after famous folks with flowing face filigrees. The Charley, defined in our unabridged dictionary as “a short pointed beard,” was named after Charles I, who, if portraits of him are to be believed (including one by the Flemish painter Anthony van Dyck… more on him shortly) rocked the pointy beard, verily—though that didn’t save him from being executed for high treason in 1649.

He was a pert, impertinent, vulgar dandy, than which nothing on earth can be more odious. He was decked out in tawdry chains and rings, all badly made, (some of them of Mosaic gold,) and wore huge bunches of ringlets over his ears, and a Charley on his under lip.

— Theodore Edward Hook, The Widow and the Marquess, Or, Love and Pride (R. Bentley, 1842)

Vandyke

: a trim pointed beard

The Vandyke is indeed named for Flemish painter Sir Anthony van Dyck (portraitist of Charles I, among others), and some believe this style involves not only an angular tuft of chin whiskers but a boffo mustachio to match.

He pulls out pocketbooks and gold snuff boxes and carbuncled cigarette-cases, and emerald eye-glasses, and curls and pomatums himself and looks in pocket looking glasses, and smooths his Vandyke beard and is a literary fop — f-o-p, fop.

— John Jay Chapman, 1896

Spinach

: an untidy overgrowth (such as an untrimmed lawn or beard)

Spinach is less a style and more of a way of life, baby. Perhaps because the leafy green plant does not grow into a tight sphere, a la cabbage and some lettuces, spinach took on a sense referring to “an untidy overgrowth” of something, including beards. The word traces back through a number of languages, including Middle English, Anglo-French, Old French, and Medieval Latin, ultimately to the Arabic word isfānākh.

Emil Herz showed up at the Waldorf yesterday and his friends immediately put him down as a truck farmer than one of the leading breeding farm owners of Kentucky, from whence he was making a flying trip. Emil was growing and displaying a fine crop of spinach on his face and declared that he would allow the whiskers to grow until he comes out of retirement from the farm on Derby Day, May 7.

—The New York Telegraph, 17 Feb. 1920

Sideburns

: side-whiskers, or continuations of the hairline in front of the ears

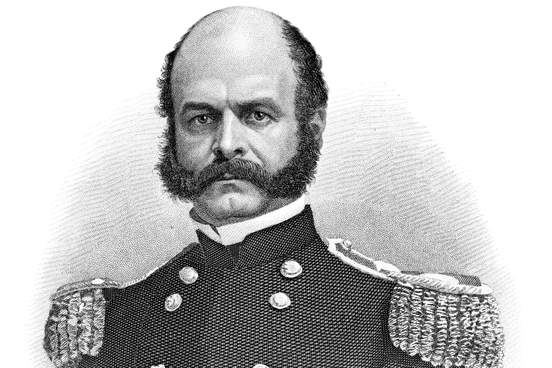

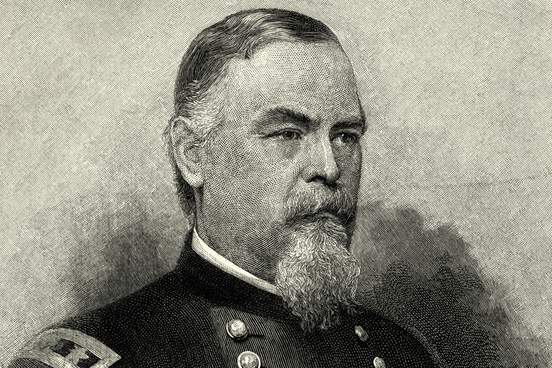

The original sideburns were called burnsides. Burnsides were a magnificent construction of facial hair, one to make any hipster jealous: thick strips of whiskers growing down the cheeks and connecting to a full mustache, but with a clean shaven chin. Burnsides owe their existence to General Ambrose Burnside, a Civil War veteran, industrialist, innovator, and Rhode Island senator. Before his death in 1881, Burnside had become a household name—not for his military service, but for his luxuriant facial hair. Burnside's facial hair was so notable that Burnside whiskers came to refer to his mustache-side-whiskers combo. Burnsides had a palpable influence not just on men's grooming, but on English, and eventually the name for the long strips of facial hair worn in front of the ears and along the cheeks were no longer called side-whiskers, but sideburns, a play on burnsides.

Petrified men continued to be moneymakers, but the game was wearing thin. In 1892, drawn by the silver boom, Jefferson Randolph "Soapy" Smith moved to Creede, Colorado. … He played the petrified-man hoax for a quick kill. His concrete giant, nicknamed McGinty, was buried and then found at nearby Willow Creek and displayed in his saloon, the Orleans Club, for an exorbitant $1 a head. … Soapy later disappeared from Creede himself, ending up in Skagway, Alaska, where he was gunned down in 1898. But just when a subject seems exhausted, someone takes it to a higher level, winning a jaded audience and overcoming growing skepticism by making the story more incredible than ever. That is what happened in 1899, when a petrified man was found near Fort Benton, Montana. Local newspapers marveled at its "neatly trimmed sideburns and mustache" and features "so perfect that a person who knew the dead man in life could not fail to recognize him now."

— Mark Rose, Archaeology, November/December 2005

Goatee

: a small pointed or tufted beard on the chin

Like many of the terms in this article, goatee sprouted in the 1800s, suggesting nothing less than a century of people staring at one another’s woolly visages and being reminded of stuff. Our (delightful) etymology for the word explains that goatee came about “from its resemblance to the beard of a he-goat,” and sometimes things (including beards) really are that simple.

Besides being the best telemarker in the group, Eric’s got an enviable goatee and knows how to drive a combine.

— Jerry Beilinson. Skiing, November 1997